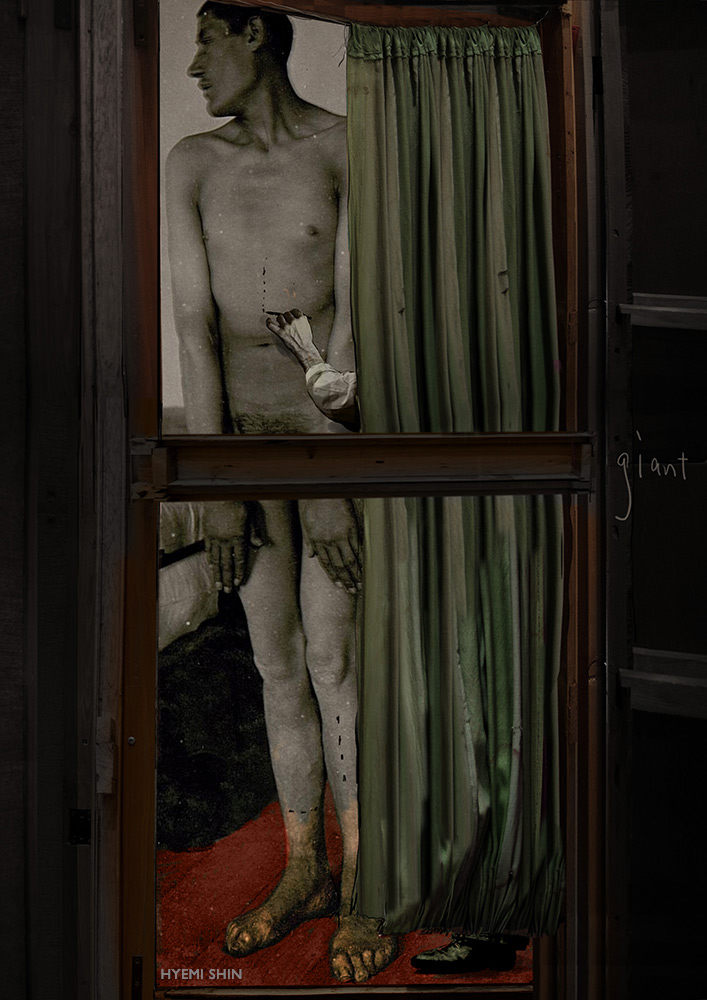

Giant (2023)

Electroacoustic chamber opera

“First, do no harm” every doctor says. But what happens when a patient’s body is so extraordinary, his corpse becomes an object of desire – a trophy?

Giant tells the story of surgeon and anatomist John Hunter and his obsession with Charles Byrne – a man he would ultimately betray in one of the most disturbing acts in the era of the grave robbers.

This debut opera from composer Sarah Angliss and librettist Ross Sutherland is directed by Sarah Fahie. The World Premiere opened Aldeburgh Festival, 9 June 2023.

Written for five voices, Giant also uses eighteenth century instruments, live electronics and the composer’s bespoke musical automata as it vividly recalls the events surrounding Byrne’s death – a disquieting story that resonates through the ages.

Giant transfers to the Linbury Theatre

Royal Opera House, London

Fri 8 – Fri 15 March 2024

Composer Sarah Angliss

Librettist Ross Sutherland

Director Sarah Fahie

Scenic designer Hyemi Shin

Costume designer Nicky Gillibrand

Lighting designer Adam Silverman

Giant premiere – Aldeburgh Festival June 2023

Photos from Marc Brenner

Men forget –

I did not craft the skull.

I made no designs upon the heart

I was not the author

of our laws of decay…

I am their enduring servant–

John Hunter

from Giant libretto (Ross Sutherland)

SYNPOSIS

Charles Byrne (1761–1783), ‘The Irish Giant’, was considered a living wonder, a freak, a gentleman, a fine performer, an ‘ill-bred beast’ and a person who held within his bones secrets which surgeon and anatomist John Hunter longed to understand.

In this fictionalised account of two extraordinary lives, John visits a London parlour, where Charles exhibits himself as a piece of living art. John is smitten by Charles’ extraordinary physique so visits him after his show, offering him money, medicine and friendship. Charles sees John as an ally but John is actually after a trade: In return for money and attention, he wants sole access to Charles’ body after death so he can dissect it and put it on public display.

Fearing this fate and the shame of his corpse becoming a public spectacle, Charles refuses John’s request. He asks his manager, Mr Rooker, to promise to seal his corpse in a lead-lined coffin, carry it to Margate and drop it in the sea. But when Charles is on his deathbed, John sends an accomplice to spy on him and intercept his funeral procession. Unbeknown to the mourners, Charles’ coffin dropped into the sea at Margate contains nothing more than rocks. His corpse has been stolen and sent to John who boils it to strip the flesh from the bones. John works so furiously on the body, he scorches the bones as he extracts them, losing evidence about Byrne’s medical condition.

John keeps his theft secret at first, then hints about it in cryptic letters to friends: ‘I have a tall man, I can’t wait for you to meet him’. In the final moments of the opera, Charles’ fate is revealed. It’s debatable how much Hunter’s professional vanity or his desire for medical progress prompted him to betray Byrne – the tragedy at the heart of this opera.

A call for restitution

It took many years for John Hunter to admit he’d stolen Charles Byrne’s body. He revealed this in stages, first in cryptic letters to friends (see above), then within a portrait, in which he instructed the painter Joshua Reynolds to depict two long legs in the shadows. Some years after Charles’ death, John put the skeleton on public display as part of his collection of medical specimens.

The events surrounding Byrne’s death occured in the 1790s, long before the era of medical consent. However Byrne’s case is unusual for the time as he made his wishes for a sea burial explicit. It was his way to escape ‘the resurrection men’ who stole corpses to order for medical teaching and research. Some argue there are reasonable ethical grounds to keep Byrne’s skeleton on display or at least within Hunter’s collection. His bones may contain useful clues for those researching pituitary tumours. Others argue it’s time for restitution: we should honour Byrne’s wishes and give him the sea burial he desired.

Update 2023: Byrne removed from public display

Byrne’s skeleton remained on public display until 2016 when the Hunterian Museum closed for refurbishment. In January 2023, museum director Dawn Kemp announced his skeleton will not be on display when the Hunterian reopens in the spring. It is no longer considered appropriate to exhibit Byrne in the public galleries – but his body will be kept for study and research.

Some see this as a good compromise, balancing Byrne’s wishes with the needs of medical researchers. However medico-legal ethicist Thomas Muinzer challenges the notion that a researcher’s interests should over-rule anyone’s wishes about their burial. This is a debate where there are no absolutes – but respecting Byrne’s privacy, two centuries after the theft of his body, seems to be an elightened step.